Public Events and Demonstrations

Tate Britain Demonstration, 2010

Intentists demonstrated outside the Tate Britain during the Turner Prize Exhibition. Intentists were concerned that some of the Turner Prize Nominees’ work was anaemic; a common result of denying authorship in art.

Tate Modern Demonstration 2010

Members of the Intentist movement demonstrated outside the Tate Modern, London on Tuesday the 23rd November.

We executed a small piece of performance art as one of our number was masked as Roland Barthes. We then handcuffed him and conducted a public trial accusing him of attempted manslaughter of the author.

We also gagged an Intentist member to illustrate our belief that much of postmodern theory has gagged the author.

We were able to distribute many leaflets and drew quite a crowd. After approximately an hour Tate managers ordered us to move on and so we set up directly opposite at the end of the Millennium Bridge. An interview with one of the Tate’s directors fell through, however, various members of the press turned out to see us.

Article on the demonstration written in -OLOGY.

RADICAL RENAISSANCE MEN

Art goes forth Breaking and entering! Police sirens! Tate hate! This doesn’t sound at all civilised, so grab a polemic paintbrush or two, as Lauren De’Ath follows the new art kids tearing up the block.

Whoever said art was all about painting a pretty picture was a downright fool. Art is about, well, art is best defined by more sophisticated minds than mine. According to some, art is a flock of sheep (Churchill, 1954); wonderfully irrational; uncompromising (Grass, 1966); a replacement for the love of god (Rushdie, 1989) and for goodness sake just be thankful that art is not a brassiere (Barnes, 1984). In a world as transient and effervescent as art, there is however one thing that’s for sure: art is provocative. And it would seem that 2011 is the year where everyone’s a have-a-go creative revolutionary.

We could summarise the past year or so in a blithe overview of radicalism: student riots, governments subverted and Middle Eastern strife. So it was only fitting that the world of art and fashion jumped on the social bandwagon, because if the shoe fits… But these guys mean business; they have websites, serious websites and PR and ‘press contacts’ and in-house photographers. They take their craft deadly seriously, especially in the war against artistic suppression. ‘Just one point: the name of our group is The Oubliette. Not The Oubliettes. This is broadly visible on our website, logo, email addresses, Facebook group et al. Cheers, Dan,’ so reads one email from self-confessed ‘Banksy in 3D’ squat-art movement The Oubliette, where a bit of foolish pluralisation means you’re in the dog house. But for all their anal corrections, Dan Simon and his motley shiny crew of artsy protesters are really just nice guys on a mission.

“We don’t pretend to be something we are not,” says spokesman Dan, “And I think people are generally appreciative of that. We’re here to run an independent arts programme, showcasing new art in new ways, independently and outside of the mainstream. We’re not squatting properties to protest about corporate greed, empty homes or the environment so anarchists look upon us with disdain, but they’re all mad so that’s quite alright. The group’s bottom line is creative freedom, and while we are not a collective, we are non-profit and communitarian.

”The Oubliette recently hit the headlines after squatting in former 80s It-club Limelight and now after grappling with the ghosts of music past (and a few bailiffs or two) they have their sights set on ‘a nice looking empty building close to Downing Street.’ At the time, Limelight was a creative man’s protest against the oppression of free speech in Belarus, however with the group inching ever further down Whitehall, who knows what’ll happen next. Living a squatter’s lifestyle, no matter how eloquent and dandy The Oubliette’s may be, certainly prepares you for the worst possible situation and whilst law dictates infamous squatter’s rights, trouble is never far round the corner. Whilst trying to break into the former Reader’s Digest building, (that I am assured is a squatter’s heaven) Dan and his unwitting accomplice Pablo leapt across London roofs to enter the erstwhile impenetrable fortress that was. “The building had been empty for over a decade and quite a number of squatters pined after it without success,” continues our paintbrush Robin Hood. “[We] found a way in via a fire escape on the roof, so we entered the neighbouring Mayfair Hotel, stole a couple of staff uniforms, bypassed security and managed to gain access. We then abseiled down the side of the building using a grappling hook and ninja rope to the adjoining roof of the Readers Digest. It was so high up we had a 360 degree panorama of the whole city. We’d just ordered the rope kit off of eBay and hadn’t had time to test it; taking the plunge over the side of the roof was fucking terrifying.”

The derring-do of The Oubliette is mimicked by events back in 2009, when a disparate group of young artists took over a boarded-up Italian restaurant and set up a raggedy sort of gallery featuring their best work. What came to be known as the 1st Gallery of Denman Street went on to spark much media interest and the six or so mop-headed boys and their shabbily dressed girlfriends became something of an infamous point du jour. “It started out as a bit of joke,” says ringleader Russian-born Sash Zyryaev. “We wanted some space and we found this old restaurant in Piccadilly from a night out and the idea just ran from there. We didn’t intend to get media interest, but we became a bit popular in the area as you can imagine. The owner Lorenzo was our biggest fan; he came down nearly every day to see what we were putting up next,” he laughs.

Of course, activist art is old hat; the twentieth century has thrown up many a feisty creative movement. Take 1976, on a busy New York City sidewalk a group calling themselves ‘Artists Meeting for Cultural Change’ are distributing posters with the headline: “ARTISTS UNITE!” It is a protest against a supposed ageist and sexist exhibition in the city and even though the exhibition still ran, the ethics were clear- we don’t take it lying down, sir. But that was the 70s, where revolution wasn’t merely a cornerstone of the decade; it was a necessity for change. It was journalist Jonathon Griffin who, whilst identifying the ironic flaws in postmodern art’s contrived polemic scene, mused: ‘Why is it so hard to imagine artists galvanizing themselves into equivalently forthright activism today?’ And perhaps he is right. In a creative world so enthralled in the wake of the macabre Chapman Brothers, has art become all about the twisted final product, rather than the message?

Cue The Intentists. They talk about such things as Roland Barthes’ death of the artist, postmodernist failings and intentional fallacy. Coming from humble beginnings, as a group that only spread news via word of mouth and shoddy A6 flyers, they had only one aim- to alter the art world for good one demonstration at a time (and via the odd guerrilla gallery in Soho). Two years after their illustrious birth, they now have followers from all over the world who share their romantic vision of ‘freeing up the artist.’

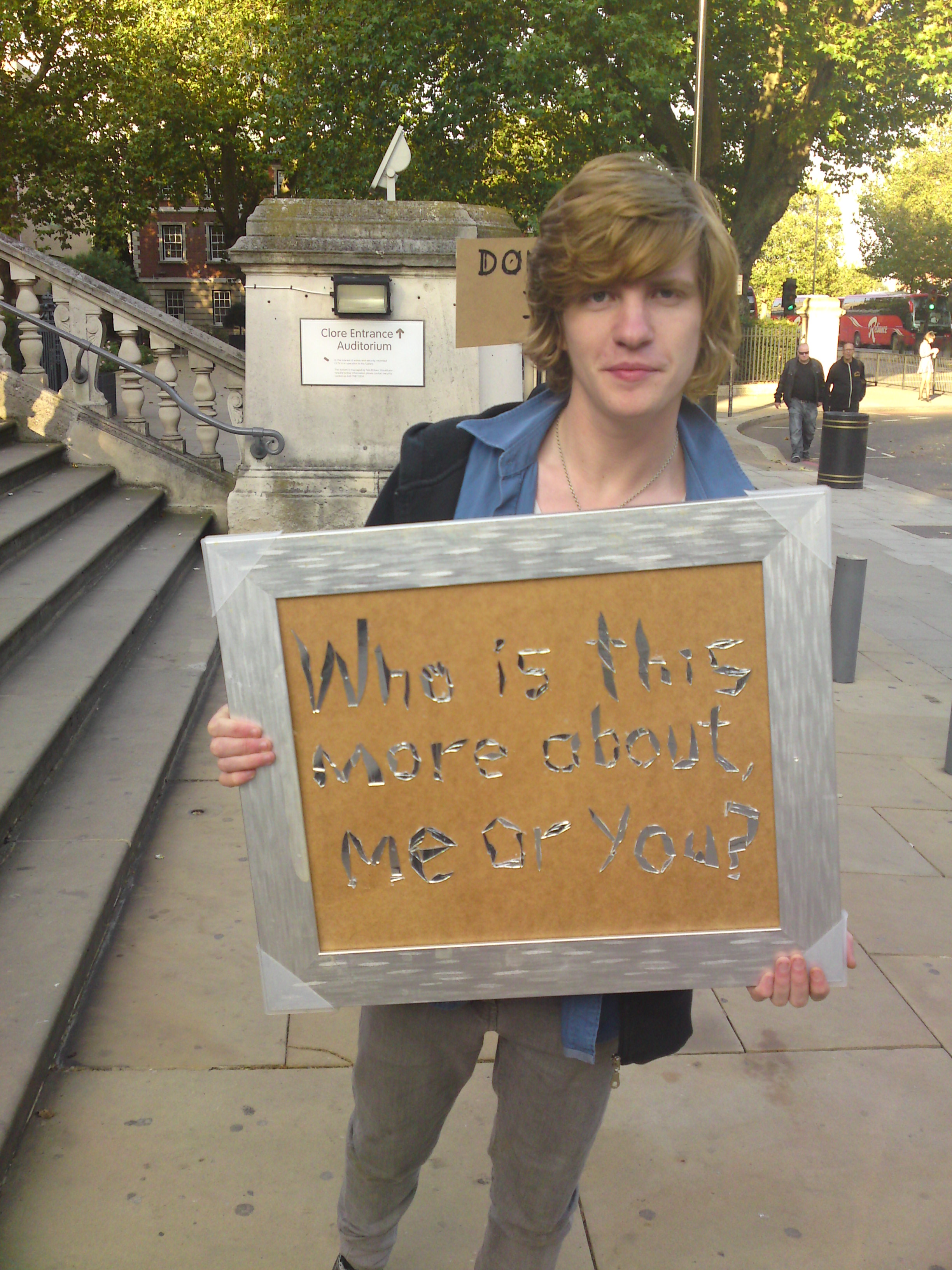

“I was talking to Brian Sewell [renowned art critic and presenter] and we were disgusted at how so many artists run away from saying what they mean and even then if meaning was found, it would be found to be irrelevant…” Now if you recall November 2010 was not a particularly predisposing month. It was windy, bitterly cold and to make matters worse we are standing in the clutches of winter besides a breezy Mother Thames. It is in such bleak seasoning that I and 35-year-old founder Vittorio Pelosi are to be found; sitting in the altogether drafty surroundings of the Turbine Room at The Tate Modern. Outside, his five most ardent cohorts (and elderly mother) are doing their utmost to cause a scene. They have assembled under a large banner; two artists have been taped to chairs, one gagged, the other masked and they have arranged an assortment of signs made from glass shrapnel to attract the eye of what few tourists wander past.

A former student of Central Saint Martins, Pelosi is a part-time lecturer and former portrait painter who’s exhibited to the likes of husky- voiced TV presenter Dannii Behr amongst others. “A lot of modern art whether popular or not has become quite anaemic,” he rants over Tate coffee. “You can’t really tell whether or not it’s been done in 1960s or now. The tragedy is that it doesn’t engage with anything that’s actually happening, economically or else and we want to change that. We want to affect all aspects of communication; in arts, literature, even the very way we speak!” Outside, his skinny-jeaned followers are shivering over roll-ups cigarettes. One boy, James, has come in to borrow some gloves.

Continues Pelosi, “Artists have been pioneers in society before and with the resurrection of the artist we believe they can be again. We want to free up the artists, to ungag him, to resurrect him… not that he ever died, but-“ Shortly after, The Intentists were asked to vacate the site by a sharply suited Tate spokes-lady called Kate.

The next time we check back into Camp Intentist, it is to some wonderful news. Pelosi, who has been writing to various broadsheet newspapers over the past two years seeking press exposure, has struck proverbial gold. “Things have been busy!” he says excitedly. “We had our annual Intentism meal in central London with [philosopher] Sir Paisley Livingstone where we discussed our major exhibition we are holding later in the year. We have been interviewed by someone writing an article about intention and translation. And a gentleman from America is beginning to make a television documentary about intention and wants to have some of our work on it.” Things are indeed looking up for the movement, so watch this space.

A bowl of sweet chili Sensations and three bottles of white wine line a round pine table. “Well, it’s a special occasion,” chimes one of Pelosi’s most ardent followers, Sydney Heighington, as he plumps cushions in a rare act of domesticity. Based in a nondescript flat a nondescript part of Limehouse, East London he totters ‘preparing’ on a pair of spindle legs around the former council premises he calls home. A corner wall of the living room is lined with scrappy line drawings that give the only clue as to what double life this humble student abode really leads, for this is the non-official home of Intentism. Amidst the hanging refuse of Sydney’s work; a portfolio that includes a broken watch strap taped to a piece of creamy A4 paper and a line of black ink gauged roughly down another inconspicuous page just beneath it, the Intentists are celebrating a successful few months. “Now you’re fucking listening,” bellows Sydney, over a glass of White Ace.

Giving Modern Art The Finger