Introduction

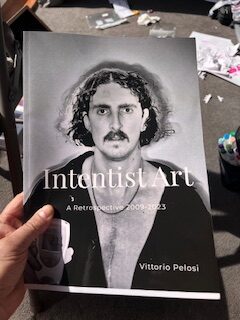

The arts movement Intentism has always focused on the importance of intention in any conversation about a work’s meaning. Indeed, the most well-known statement form the Intentist Manifesto is ‘all meaning is the imperfect outworking of intention.’ However, with the rise of AI and in particular LLMs, we have texts that can be understood and even engaged with that did not come from a human mind. It has been said that AI has shown something that nobody could have predicted- namely that we can have intelligence without consciousness. This essay will briefly look at how human might work with AI and how this collaboration might shape our understanding of authorship and intention. Questions that are pertinent include: If meaning is contingent on intent, then where does intent reside in human-machine collaborations? Does it lie solely with the human creator, or can AI systems develop a form of intent? If neither, does the partnership itself generate a new kind of distributed intentionality?

There seems to be three sources for locating intent in any human, AI partnership.

1. Human-Exclusive Intent – Intent remains solely with the human author, with AI serving as an advanced tool.

2. Emergent Intent – Intent arises from the interaction between human and machine, forming a hybrid agency.

3. Simulated Intent – Although not conscious, AI mimics intent well enough that, for practical purposes, it can be treated as a creative agent.

1. Human-Exclusive Intent: AI as an Advanced Tool

The most conservative Intentist position maintains that intent can only reside in human creators because AI lacks consciousness, agency, and subjective experience. One commonly used slogan from Intentists is ‘No creative input, no meaning input.’ From this perspective, AI is no different from a paintbrush or a word processor—an instrument that extends human creative capacity but does not contribute meaning independently. This sems to be the most naïve position. Let’s look at it more carefully.

i) The Chinese Room Argument (Searle, 1980). An AI can simulate understanding (e.g., generating a poem) without actually comprehending it, just as a person manipulating Chinese symbols without knowing the language can produce coherent responses without genuine intent. The Chinese Room experiment has been one of the most significant contributions to the philosophy of language and Intentists have generally been very influenced by it. However, critics might argue that the way the brain interprets signs in language is actually not too different from the Chinese Room.

Dependence on Training Data. AI models like DALL·E and ChatGPT derive their outputs from human-created datasets, meaning their “creativity” is a recombination of pre-existing human intent rather than original thought. This is similar to Barthes’ famous quote in his seminal work ‘The Death of the Author.’ In it he said that ‘All language is a textile of quotations’ meaning that every utterance is a collating together of words, collocations and expressions that we have heard before. In many ways, LLMs are also similar in that they are similar to a super intelligent predictive text- as they look at huge corpora (quotations) and reuse these pre-fabricated chunks of language.

ii) No First-Person Experience. AI lacks desires, beliefs, or goals—essential components of intentionality in the philosophical sense (Brentano, 1874). Critics here might point out that a LLM that answers a prompt does have, albeit it in a limited sense, a desire, belief or goal to answer the prompt. Moreover, if the human provides detailed prompts and engages with the LLM’s answer, does this not make the AI more of a collaborator than a tool? Furthermore, sometimes the AI model generates an unexpected result that was not asked for by the human author. If this is the case, can the human claim full authorship?

2. Emergent Intent: The Hybrid Agency Model

Emergent intentionality suggests that when humans and AI collaborate, the interaction itself produces a new form of distributed intent—one that is neither fully human nor machine but a product of their interaction. This aligns with theories of extended cognition (Clark & Chalmers, 1998), where tools become part of the cognitive process.

There are various examples that might support this.

i) Interactive Feedback Loops: In tools like AI-assisted music composition, the human refines outputs iteratively, creating a dialogue where intent evolves dynamically. This, it must be said, is not solely the domain of AI assisted music composition. Part of understanding human creativity is the experience of musician composing a section of music, only for the impact of that to make him reassess other parts of the composition. In essence, there has always been a dialogue between a defined intention and what materializes that is refined iteratively.

ii) Distributed Creativity in Art History: Similar debates have arisen with photography and digital art—tools that introduced new creative agency beyond the artist’s direct control. Can we always define a work by the artist’s original intention? Intentists have historically never had a problem with this. Intentists have argued that artists often have a macro intention and numerous micro intentions. These micro intentions might alter the original macro intention. Moreover, in photography, sometimes the camera and the happenstance composition is tremendously important to the work. Intentists here have argued that much of the photographer’s intention and creativity is in the editing process.

iii) Posthumanist Perspectives: If creativity is not confined to individual human minds but can emerge from systems (e.g., hive minds, algorithmic processes), then AI partnerships could generate a new kind of “cyborg authorship” (Hayles, 1999).

Some of the most common arguments for Intentism are relevant here. Firstly, emergence imply consciousness? Does AI genuinely feel sad, or elated. Humans know we are mortal and have feeling of loss etc. Without AI possessing subjective experience, can emergent intent truly exist, or is it just a useful metaphor?

A second major concern of Intentists that even finds its way into their Manifesto is related to responsibility. One of the concerns with postmodernist arguments that the author is dead relates to this. If a writer writes inflammatory and offensive material, can he still be accountable? Equally, if an AI-assisted novel contains plagiarized or offensive content, is the human, the AI, or the partnership to blame?

3. Simulated Intent: AI as a Functional Agent

From a pragmatic standpoint, if AI behaves ‘as if’ it has intent—generating contextually appropriate art, explaining its creative choices, and adapting to feedback—then for all practical purposes, it can be treated as an intentional agent. This aligns with Dennett’s *intentional stance* (1987), where we attribute intent to systems that are complex enough to warrant such interpretation. One of the simplest arguments for intention in understanding meaning comes from Livingston’s Art and Intention where he discusses a parrot’s speech. The owner of the parrot might teach it to speak all sorts of complex and clear dialogue but you would not ascribe meaning to it. For example, if a parrot said something racist or demonstrably wrong, you would not correct it. The parrot has no ability to explain what it has said or adapt to feedback. However, AI- though arguably less aware in a philosophical sense of its output than the parrot, is able to converse and behave in a way that simulates intention.

i) Explainable AI (XAI). Modern AI can articulate its “decisions” (e.g., “I chose this colour palette for emotional contrast”), creating the illusion of deliberate choice.

ii) Audience Reception:** Many people already engage with AI art as if it were created by a sentient being, suggesting that perceived intent may be socially constructed. It is of interest that AI is at present very agreeable. The result of this is that it is not uncommon for the human to either praise or thank the AI for its contribution

iii) Legal & Economic Precedents: Corporations are treated as “legal persons” despite lacking consciousness; could AI eventually occupy a similar role in creative industries?

One of the major arguments of this position is the infamous ‘Hard Problem of Consciousness. We have no idea how to define consciousness, let alone analyse it. Simulation is not equivalent to genuine intent (Chalmers, 1995).

Surely, the idea of simulated agency is of interest but it blurs the line between real and illusory agency.

In conclusion, perhaps a ‘graded intentionality spectrum’ may be needed.

1. Low Autonomy AI (e.g., Photoshop filters):Intent remains fully human.

2. Moderate Autonomy AI (e.g., GPT-4 with human curation): Intent is shared but human-dominated.

3. High Autonomy AI (e.g., self-modifying generative agents): Intent approaches functional equivalence, even if not philosophically “real.”

Either way, it is important to maintain the Intentist position that meaning is rooted and grounded in agency and intention. The argument then would be if this must be human and ‘real’ or AI ‘unreal’ but functionally analogous.